- +91 9096131868

- falconedufin@gmail.com

- All Day: 10:30 AM - 9:30 PM IST

How can we help you?

The Building Blocks Of Risk Management – FRM 2023

Reading Time: 12 min read

Learning Objectives #

- Explain the concept of risk and compare risk management with risk-taking.

- Describe elements, or building blocks, of the risk management process and identify problems and challenges that can arise in the risk management process.

- Evaluate and apply tools and procedures used to measure and manage risk, including quantitative measures, qualitative assessment, and enterprise risk management.

- Distinguish between expected loss and unexpected loss, and provide examples of each.

- Interpret the relationship between risk and reward and explain how conflicts of interest can impact risk management.

- Describe and differentiate between the key classes of risks, explain how each type of risk can arise, and assess the potential impact of each type of risk on an organization.

- Explain how risk factors can interact with each other and describe challenges in aggregating risk exposures.

Note: There are two approaches to study this topic (also applicable for all the other theory topics of this book).

- Approach 01: Start FRM preparation with this topic (or this book). This approach is recommended only for students who are well versed with finance and risk management industry. If you are new to this industry, I would recommend you to use approach 2 to avoid all the pain of studying this topic.

- Approach 02: First finish preparation of Book 2, 3, 4 and CAPM APT topics from Book 01 and then study Book 01 theory topics. Because most of the terms required to understand this reading (and other theory readings of Book 01) are discussed in detail in other books which will reduce friction in preparation of this topic.

Please read note given on the previous page before reading this topic.

Introduction #

Risk is essentially the likelihood that undesirable things may occur. The first autonomous financial risk transfer mechanism was created in northern Italy in the thirteenth century when the insurance contract separated from the loan contract. Risk mathematics began to be studied more methodically in the seventeenth century. This was followed by the development of exchange-based risk transfer in the form of agricultural futures contracts in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Types of Risks #

Market Risk #

Market prices and interest rates fluctuate, causing the value of securities and other assets to rise and fall. Because price volatility is the source of market risk, these swings create the possibility of loss. Market risk can manifest itself in a variety of ways depending on the underlying asset. From the standpoint of a financial institution, the most important types are stock risk, interest rate risk, currency risk, and commodity price risk.

Market risk is driven by the following.

- General market risk: This is the risk that an asset class will fall in value, leading to a fall in the value of an individual asset or portfolio.

- Specific market risk: This is the risk that an individual asset will fall in value more than the general asset class.

The correlations between positions can be used to manage market risk. A large equities portfolio’s diversification benefits, for example, form the foundation of investment risk management.

However, market risk occurs as a result of these interrelationships. For example, an equity portfolio meant to mirror the performance of an equity market benchmark may underperform it—a type of market risk. Similarly, a position designed to balance off, or hedge, another position or market price behaviour may do so in an imperfect way—a type of market risk known as basis risk.

This mismatch of price fluctuations is frequently a bigger challenge for risk managers than any single market risk exposure. A commodities risk manager, for example, may be using crude oil futures to hedge jet fuel, only to discover that the regular price differential between the two has expanded.

Credit Risk #

Credit risk emerges when one party fails to fulfil its financial obligations to another. Some examples of credit risk are as follows:

- A debtor fails to repay loan (bankruptcy risk);

- An obligor or counterparty is credit rating is downgraded (downgrade risk)

- A counterparty to a market trade fails to perform (counterparty risk), including settlement or Herstatt risk.

The possibility of default of the obligor or counterparty, the exposure amount at default, and the amount recoverable at default indicate credit risk (EL = PD X LGD X EAD, ref Book 4 credit risk). A firm’s risk management approach can influence these levers, including the quality of its borrowers, the credit instrument’s form (e.g., whether it is heavily collateralized) and exposure controls.

Most loans have a clear level of exposure, while some transactions can be uncertain. Derivatives, for example, have no immediate market value and thus no credit risk. The position can develop a major counterparty credit exposure if markets move.

Risk variables are identified and evaluated to determine the likelihood of an obligor defaulting. Some financial indicators and industry sectors are used in corporate credit risk analysis. However, obligor concentration and the combination of risk factors define the risk in total credit risk portfolios. The portfolio will be significantly riskier if:

- It has a small number of large loans rather than many smaller loans;

- The returns or default probabilities of the loans are positively correlated (e.g., borrowers are in the same industry or region);

- The exposure amount, probability of default, and loss given default amounts are positively correlated (e.g., when defaults rise, recovery amounts fall).

Risk managers utilise sophisticated credit portfolio models to identify risk posed by various risk factor combinations.

Liquidity Risk #

Liquidity risk is used to describe two quite separate kinds of risk funding liquidity risk and market liquidity risk.

Funding liquidity risk #

Is the risk that a corporation will not have enough liquid cash or assets to pay its obligations. All businesses face funding liquidity risk. For example, many small and developing businesses struggle to pay their payments quickly enough while still investing for the future.

Banks face a unique type of funding liquidity risk due to their business model. For example, banks strive to take in short-term deposits and lend them out longer-term at a higher interest rate. To reduce risk, good asset/liability management (ALM) is essential in the banking industry. ALM uses techniques like gap and duration studies.

Market liquidity risk #

Trading liquidity risk is the risk of asset value loss when markets abruptly seize up. As a result, a seller may be forced to accept an abnormally low price, or lose the power to convert an asset into cash and finance at any price. Market liquidity risk can quickly become financing liquidity risk if banks rely on volatile wholesale markets to raise cash.

Market liquidity risk is difficult to quantify. In a regular market, liquidity is measured by the number of transactions and the bid-ask spread. However, these are not always reliable indications of market liquidity in a crisis.

Operational Risk #

Insufficient or failing internal procedures, people, and systems, or external events, constitute operational risk. It excludes business, risk, and reputation risk.

From anti-money laundering and cyber hazards to terrorist attacks and rogue trading, that’s a broad definition. During the 1990s, rogue trading helped regulators integrate operational risk in bank capital calculations.

Beyond the banking business, many company tragedies might be classified as operational risk. These include physical operational failures and corporate governance issues, as the 2001 Enron debacle. Many risk managers outside the financial industry focus on operational risk management, frequently through insurance solutions.

However, defining and measuring operational risk remains difficult, particularly in the financial sector.

Business and Strategic Risk #

Business risks include client demand, pricing decisions, supplier agreements, and managing product innovation. Business risk is not strategic risk. Major strategic decisions generally involve significant cash, human risk, and management reputation investments.

Business and strategic risks occupy most of management’s attention in non-financial organisations, as they definitely do in financial firms. But it’s not clear how they link to other hazards or how they fit into each firm’s risk management system.

For exam please note: Business risk is the risk in ongoing business (in current state) however, strategic risk involves risk in expansion plans, new prototype development etc.

Reputation risk #

Most reputation risk occurs when another area of risk management fails, causing loss of faith in the firm’s financial stability or reputation for fairness.

For example, a big credit risk management failure might lead to financial concerns. Rumours can be deadly. Investors and depositors may start withdrawing support in anticipation of others. Banks must prepare plans to reassure markets and restore their reputations. Fairness is also important. There are certain expectations for big businesses. Erroneous product risk disclosure might cost a company valuable clients.

Regulators’ reputation is crucial to financial organisations. Regulators possess significant informal and formal power. If a regulator loses trust in a bank, its actions may be criticised or limited.

Risk Management Process #

We take risks for reward, be it food, shelter, or bitcoin. But the real questions are: is the reward worth the risk, and can we reduce the risk and still achieve the return? To answer these questions, we need our first building block: the risk management method.

Risk management process:

- Identify the risk: Identify the risk to which firm is exposed.

- Analyse Risk: Understand the risks nature.

- Assess impact of risk: Quantify the risk and asses the impact on the firm.

- Manage Risk: Take the steps to manage the risk(discussed in the next point).

Choices in risk management process:

- Avoid Risk: There are dangers that can be avoided by closing the business or changing the strategy. Exporting to specific markets or outsourcing production may be avoided to reduce political or currency concerns.

- Retain Risk: Some risks are within the firm’s risk appetite. Captive insurance and risk capital allocation can maintain large risks.

- Mitigate Risk: Exposure, frequency, and severity can all be reduced (e.g., improved operational infrastructure can mitigate the frequency of some kinds of operational risk, hedging unwanted foreign currency exposure can mitigate market risk, and receiving collateral against a credit exposure can mitigate the severity of a potential default).

- Transfer Risk: With derivatives, structured products, or paying a premium, certain risks can be transferred (e.g., to an insurer or derivatives provider).

In order to explore additional value-creating possibilities for its stakeholders, the risk taker must strengthen its risk management strategy. Risk management investment allows farmers to grow more food, metal companies to create more metal, and banks to lend more money. Firms can excel with risk management.

In modern economies, risk management is about more than just survival. It’s vital to specialisation, scale, efficiency, and wealth development.

That’s why risk never goes away. Success in risk management paves the way for more. The risk manager must constantly discover, evaluate, and manage risks to avoid exposing the organisation to unnecessary risk. Identifying and analysing risk in a rapidly changing world remains difficult.

Known vs unknown Risks #

One of the most common errors is to focus on known and measurable hazards while neglecting unknown or undefined threats.

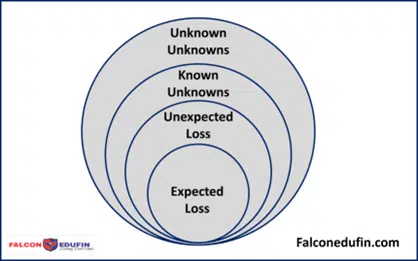

Figure 1.5 depicts a basic classification of known versus unknown risk. Individuals tend to focus on recognised risks and neglect new or poorly understood risks. But the hazards must be handled.

Knightian uncertainty (known unknown) is tremendous. The likelihood of nuclear war is uncertain but impact is huge. Risk management can help avoid or manage Knightian uncertainty. To take bold measures, everyone must acknowledge the Knightian uncertainty (if unquantifiable in terms of frequency).

Uncertainty and quantified risk are distinct concepts. Risk of non-measurable risks is the duty of risk managers. They must constantly look for “unknown unknowns,” including hidden risks. They can’t overlook Knightian doubts. They must sometimes ensure their firms avoid or transfer them. Risk managers shift poorly understood hazards closer to the centre of Figure 1.5. Knightian doubts can be more severe and widespread than we think. Risk managers must never approach unknown threats as if they are known. Uncertainty and ambiguity exist in greater levels for some risky activities than others. Our faith in a risk metric influences how it should be used in decision-making.

Risk Measurement #

Risk can be measured as quantitative and qualitative risk measures. This you don’t need to separately focus on this section because it is discussed in detail across the FRM curriculum in different sections (mainly different chapters from Book 4).

Quantitative Risk measurement Tools

- Value at risk

- Expected loss measure

- Unexpected loss measure

Qualitative Risk Measurement Tools

- Stress Test

- Scenario Analysis

Risk and Reward Relationship #

A VaR technique can assist the organisation to compare the risk exposures of different business lines. Firms learn to expect and avoid losses associated with certain activities. The firm can also protect itself by ensuring that its risk capital (also known as economic capital) is sufficient to absorb any unforeseen risk.

Economic capital, often known as risk capital, is the amount of capital a bank needs to manage its economic risks. Regulatory capital is estimated according to regulatory rules and techniques. Economic and regulatory capital typically overlap, although the amounts are often quite different. Economic capital allows the corporation to conceptually balance risk and profit. Firms can compare their revenue and profit to the quantity of economic capital necessary to sustain each activity.

These risk capital costs can subsequently be factored into product pricing and business line performance comparisons. There are evident causes. For example, Business A may incur high annual EL expenditures but little unforeseen losses. Contrarily, Business B may receive minimal EL but suffers huge losses at the conclusion of every business cycle.

It’s difficult to evaluate Business A and B’s profitability without comprehensive risk-adjusted research. During the benign cycle, Business B is likely to be quite appealing. The firm may opt to lower product prices to increase sales. When the cycle turns, this typically results in losses. Global banking businesses have tended to behave in this way, compounding the tendency for economies to boom and crash.

To factor in the cost of risk of both expected and unexpected losses, the bank can apply a classic formula for risk-adjusted return on capital (or RAROC):

RAROC = Reward/Risk

Where reward is described as After-Tax Risk-Adjusted Expected Return and risk as economic capital.

After-Tax Net Risk-Adjusted Expected Return also needs to be adjusted for Expected Losses:

RAROC = After-Tax Net Risk-Adjusted Expected Return/ Economic Capital

To provide value to shareholders (and the stock price), RAROC must exceed the cost of equity capital (i.e., the hurdle rate or minimum return on equity capital required by the shareholders to be fairly compensated for risk).

The RAROC formula has several applications in various sectors and institutions. Though sophisticated, they all serve the same purpose: adjusting performance for risk. Four everyday uses stand out.

- Business comparison: RAROC allows organisations to compare the performance of different business lines.

- Investment analysis: A firm often utilises the RAROC method to assess prospective investment returns (e.g., the decision to offer a new type of credit product). RAROC findings can also be used to examine if a business line is delivering a return above a hurdle rate set by the firm’s equity investors.

- Changing pricing strategy for different customer categories and products. For example, it may have set prices excessively low to achieve a risk-adjusted profit in one business sector while increasing market share in another (and overall profitability).

- Risk management RAROC assessments can assist a corporation compare the cost of risk management (e.g., risk transfer via insurance, to the benefit of the firm).

Applying RAROC is problematic due to its reliance on the underlying risk estimations. Business lines frequently contest the veracity of RAROC statistics. Like other risk measures, decision-makers should always comprehend the number’s meaning and context.

Updated on October 11, 2022